Close and Slow: 'Michael Longley Reads Harmonica' by Ian Duhig

A Weekly Appreciation of Poetry

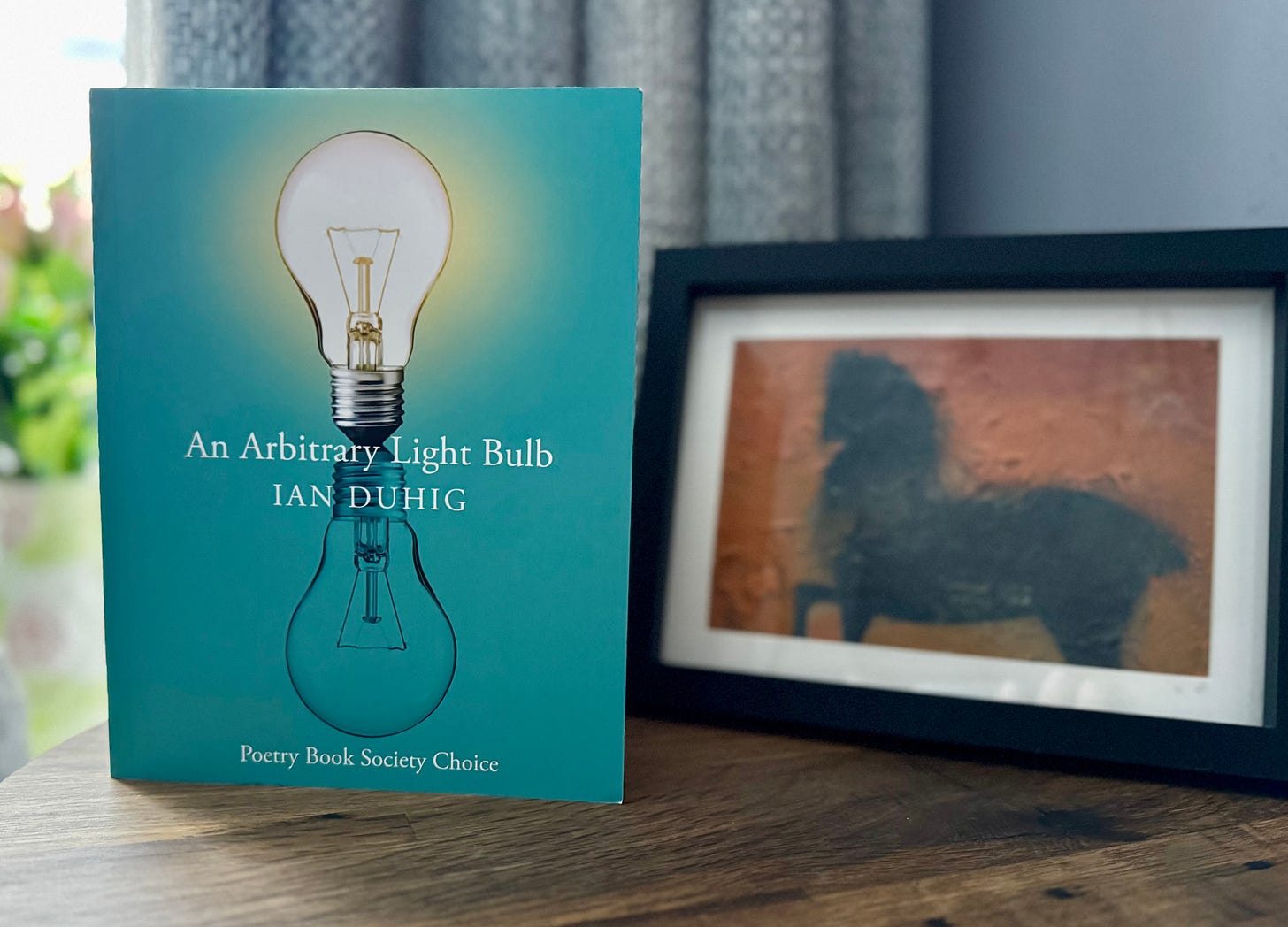

The passing of Michael Longley continues to cast a long shadow over the world of poetry. Over the next while readers should expect to see some periodic articles on The Sounding Board, reflecting on his body of work and his legacy. This is once again reflected in this week’s ‘Close and Slow’ where our focus will be on a new poem from Ian Duhig. The poem,…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to New Grub Street to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.