Köln Revisited

Or why our art needs this non-ideal world

A number of years ago, I wrote an article on what has come to be known as The Köln Concert. In this piece, I want to revisit this amazing cultural moment and share some thoughts that spring from it about our own creative work.

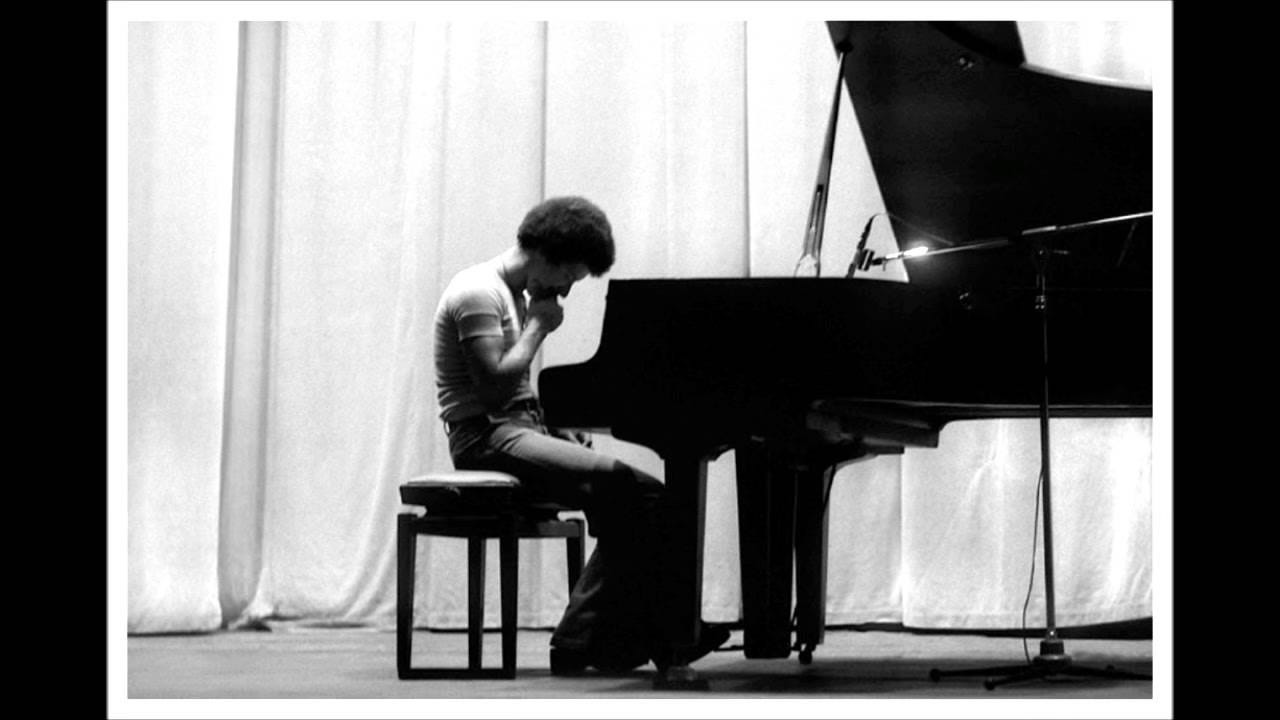

It’s January 24th 1975, and pianist Keith Jarrett is scheduled to play a concert in the city of Köln. It will go down in history for two reasons: the fact that it is a hopeless failure, and that it will be a roaring success.

Murphy’s Law Under Laboratory Conditions

Let me explain. Everything that could have gone wrong with regard to this concert did. Jarrett hadn’t slept on the night before and had to travel from Zurich with such roaring pain in his back that he needed a brace. The concert was organised by 17-year-old Vera Brandes and, as it was not the ‘done thing’ for jazz concerts to take place in Köln Opera House, the performance had to be scheduled for 1130pm. To cap it all, the wrong piano was placed on the stage. Jarrett had requested (and Brandes had ordered) a Bösendorfer Model 290 Imperial, but the stage crew had brought a different, smaller, inferior Bösendorfer model. This instrument was a pianist’s nightmare, needing to be tuned for hours, and lacking the required range to be used for a concert. The mistake was irreversible, and Jarrett had to be coaxed to go on stage. This was Murphy’s Law under laboratory conditions.

The outcome - known now as the Köln Concert - was a masterpiece, and has become the largest-selling piano album in history. The weaknesses of the instrument meant that Jarrett had to employ every device in his power to make it play, emphasising the mid-range of the piano because that was where it was strongest. The music produced is unique, powerful, urgent and vivid. This was the wrong instrument, played in the worst of circumstances, to produce incredible beauty.

Our Creativity Under Köln Conditions

In thinking about creative work (and any kind of labour or endeavour), it is good to be reminded of the Köln concert. As a writer and editor, I can easily get swept up in the romanticism of what it is to fulfil these callings. Social media and movies portray writing in the most idyllic of terms - the author or poet sequestered in a lakeside home, Mid Century Modern furniture communicating space and quietude and intellectual clarity. The tweed bedecked, or corduroy author is tucked behind their typewriter, glass of Scotch within easy reach, the clatter of keys and ding of the carriage their soundtrack for the creation of some Great Work.

Speaking for myself, writing and editing seldom look like this, and more often than not, I am working in Köln concert conditions. Work on the things that matter most often emerges from the mess of getting through everyday life, with its contingencies and interruptions, with my insecurities and manifold distractions, and where prime conditions seldom present themselves. This is so often the case that when I find myself in some ideal circumstance for reading, researching or writing, I can’t actually work because it is lacking the white noise of things happening around me that I need to address, overcome or tune out.

As I make regular revisits to Jarrett’s moment of beleaguered genius, I find myself repeatedly impressed by the sounds of approbation that he makes, the little cries of adulation as he enters the flow of his music amid everything being a little out of joint. This is surely where the true work takes place, among all of the sensory interruptions, the dampened keys of creative labour, the clatter and bang of everyday life - and there are those moments where pen and paper kiss in happy reconciliation, where the keyboard becomes a conduit for writing that surprises me and moves me, even if it never sees the light of day or is read by another soul.

Creative friend, I want to encourage you that the setbacks and detractions that your life and environment present you with might actually be the very things that will be the making of your work. I think of TS Eliot returning to the town of Marlow to his upstairs flat after a day working in the bank, and writing The Wasteland. I think of James Joyce living in Trieste and reimagining Dublin City, I think of George Orwell on the Isle of Jura producing a book in the last years of his life, which continues to shape and warn our minds in the midst of totalitarianism.

Nothing is perfect about how art is made, and no art that is made can hope to be flawless. What we produce carries the aroma of the life we are living around it, and it is all the better for it. Keith Jarrett could have limped out of the Köln Opera House, refusing to perform in light of the mistakes that others had made and the lateness of the hour. Instead, he sat down at the piano and exploited the limits his world had placed on him, producing a work of genius in which his soul is clearly invested.

It is good for me to remind myself of what limitation produced in Köln all of those years ago and to adopt Leonard Cohen’s sage words as my very own anthem. Perhaps they could be yours as well.

Ring the bells that still can ring Forget your perfect offering There is a crack, a crack in everything That's how the light gets in.