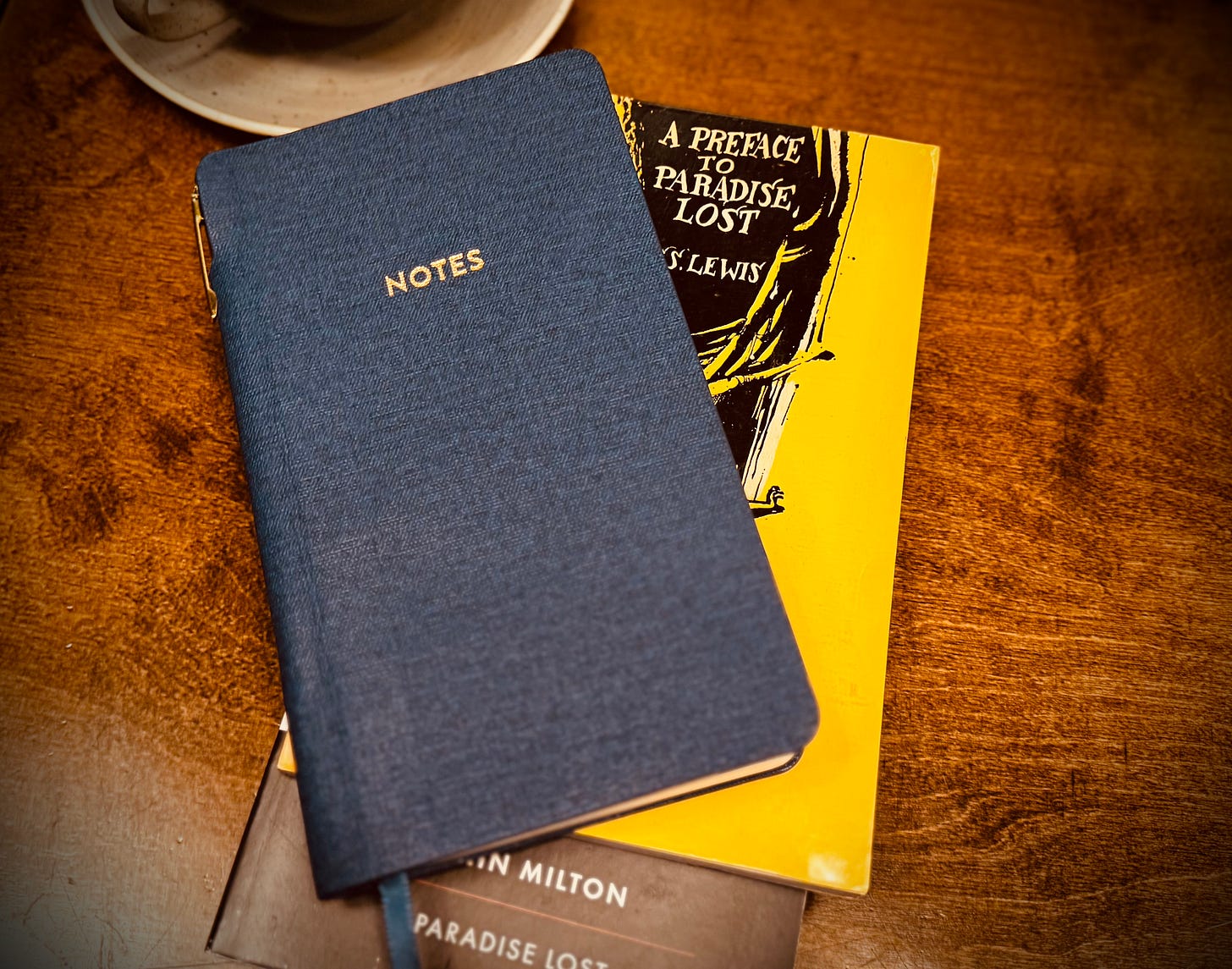

Lost with Lewis Pt.4

Reading Milton with some help from a friend

An ongoing Substack series by Karen Swallow Prior over at The Priory is stimulating lots of reading and discussion of John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost. Even though I’ve loved literature for years, I have never read through this work from start to finish, and I am grateful to have such a gracious and knowledgeable guide to help me through it. As a s…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to New Grub Street to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.