Monseigneur Bienvenu’s Lesser Known Meeting

How Victor Hugo’s Bishop instructs us about difference

Over the past couple of weeks, I have been doing a deep dive in Victor Hugo’s enormous novel Les Misérables. I am somewhat late to the party in only reading this major work now, but the book is landing major lessons and challenges that feel well-suited to midlife. Please expect some Les Misérables inspired posts over the next while!

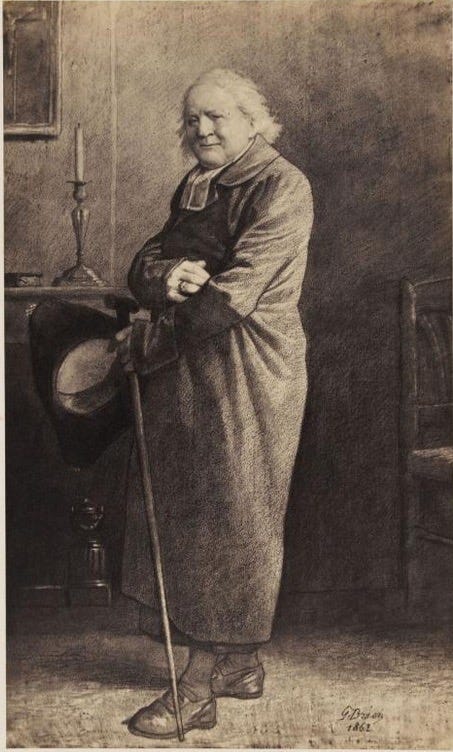

The early chapters of Les Misérables introduce us to one of the most compelling Christian cameos in all of literature - the figure of Bishop Charles-François-Bienvenu Myriel, affectionately known as Monseigneur Bienvenu. The attitude and actions of this character are held up by Hugo as a kind of ideal, as an embodiment of applied Christianity and liberal values. Bienvenu whose kind and counter-intuitive conduct forms the moral backbone of the novel, is above all things a Christian man. His concern for the least, his love for those who have lost their way, and his gentle strength in handling the haughty all come under the spotlight in Hugo’s construction of him as a character.

The Bienvenu section of the novel is quite long, with Hugo investing significant effort into constructing him as a believable and loveable person. Out of all of this detail, one episode tends to predominate in the popular imagination - the release of Jean Valjean from the charge of theft through Bienvenu’s surprising grace. In many ways, this is exactly as it should be, given how influential this act is on Valjean’s character development.

There is, however, another meeting between Bienvenu and a social outcast that is equally telling and powerful. In chapter 10 of Book 1, Bienvenu pays a pastoral visit to an old member of the Convention that oversaw the French Revolution and ultimately the execution of the country’s King. This man is so despised and marginalised that the path to his home is overgrown and he (simply referred to as G) is a kind of bogeymen figure for the parish of Digne where Bienvenu serves.

The whole episode serves as a model for dialogue with, and grace towards, those who are ideologically different from us and has a lot of enduring cultural relevance, which I will attempt to unpack below:

Engaging with difference is an act of grace

Monseigneur Bienvenu, otherwise unflappably gracious in the section of Les Misérables that he occupies, finds the prospect of visiting G repulsive. Living as he does in the Bourbon Restoration period of French history and keenly conscious of the abuses perpetrated by the Convention, the bishop allows himself some quite well-grounded prejudice. He, along with the rest of his town, holds G in disregard and there is a sense that the clemency from the French state that allowed such men to live in the country unmolested is ill placed.

Word reaches Bienvenu that G is dying. This fact creates an inner tension in the Bienvenu who eventually privileges the requirements of his pastoral office over his prejudicial misgivings,

The bishop would reflect and from time to time gaze at the horizon where a clump of trees marked the old member of the Convention’s valley, and he would say, ‘There’s an isolated soul out there.’ And deep in his own mind he added, ‘I owe him a visit.’

This pastoral conviction leads Bienvenu to journey to the old man’s home and to make contact where others have perpetuated exile. The bishop finds a stern sense of antipathy rise in him on meeting G, but his presence at his home in his dying hour is an act of costly grace.

Hugo constructs this scene meticulously, and the reader can feel the inner tension that rises in the bishop’s soul at the prospect of engaging with such an ideological opposite. But he does go, he does walk the overgrown path to a political adversary, albeit armed with a strong feeling of antagonism.

As with so much in the Bienvenu section, the reader is being invited to contemplation and imitation. The contemporary parallels are striking, in which opposing ideological views are becoming increasingly entrenched and polarised. Taking the step to enter the world of another person, to scale the barbed wire of contrary beliefs and to take time to talk is costly work, but crucial to the intellectual and moral health of a community. Such forays into the foreign territory of opposing beliefs might be brief and confirmatory of one’s own position but on the other end of all opposing ideology is a person who most likely holds their belief in good faith. Bienvenu’s journey makes me question how I view my ideological opposites and how willing I am to sit on their porch in order to listen.

Engaging with difference is an opportunity to learn

Bienvenu’s visit to G is a surprising episode for the bishop. His initial coldness and sternness in approaching the old man’s home is quickly overcome by the tone and tenor of the conversation the two men share. G, though close to death, is physically robust and intellectually agile, proving to be a strong ideological opponent for the bishop.

Talk between the two men quickly turns to to the past and to politics. What disarms Bienvenu is the humanity and integrity of G’s views, which when aired fully and without prejudice, more than answer the bishop’s own arguments. G is not an ogre, his part in the Revolution was not unthinking or unfeeling and he is able to identify common moral wrongs on the part of the Convention and the Church. Perhaps most surprising of all, this man believes in God and makes a confession of sorts towards the end of the dialogue.

Bienvenu is disarmed and, in a moment that Hugo must have taken great delight in writing, ultimately bows before the dying man to receive a blessing rather than to dispense one.

The effect of this boundary-crossing meeting on Bienvenu is lasting and positive. Having made contact with the social conscience of G, his life’s focus becomes even sharper,

From then on, his kindness towards the humble and the unfortunate and his fellow-feeling for them increased.

This episode, less famous than the bestowal of silverware and forgiveness on Valjean, is worthy of our attention and imitation. One of our best ways to be more fully rounded in our views is to be generous and attentive to our intellectual opposites. There is grace and learning to be found in the company of those whose views are utterly at odds with our own. From my own position, Christianity has often done badly in its listening, rushing to ‘other’ and ostracise rather than listen and learn. Such learning does not require us to change our views but it might moderate them, or at least inform them of the humanity and decency that can underpin different positions.

The same could be said of any ideological convictions we hold to. The feet of Bienvenu may just have worn a path for us to follow, into the overgrown territory of other opinions and worldviews. It takes courage to walk this way, but the end result is more than worth it.

I have not read this book yet, but am now intrigued by what you've written here. I have only attended the plays and seen the movie. Surely the book is better than the movie, as in most cases. What translation are you using, please? Thank you for this!

Sadly in the Evangelical church, difference is often the doorway to division. One Denomination has their favourite Theologian and bangs his drum weekly. Another Denomination doesn’t bang his drum at all, possibly doesn’t even believe literal drums should be in the church… 🙂 …but because there’s ‘difference’, there’s division, them and us. Those of Paul and those of Apollos, but both are in Christ, in whom there is no division, and want those outside of Christ to come into the unity of His Body the church.